REFLECTION: Print Making and Drawing

Print making, making as multiple

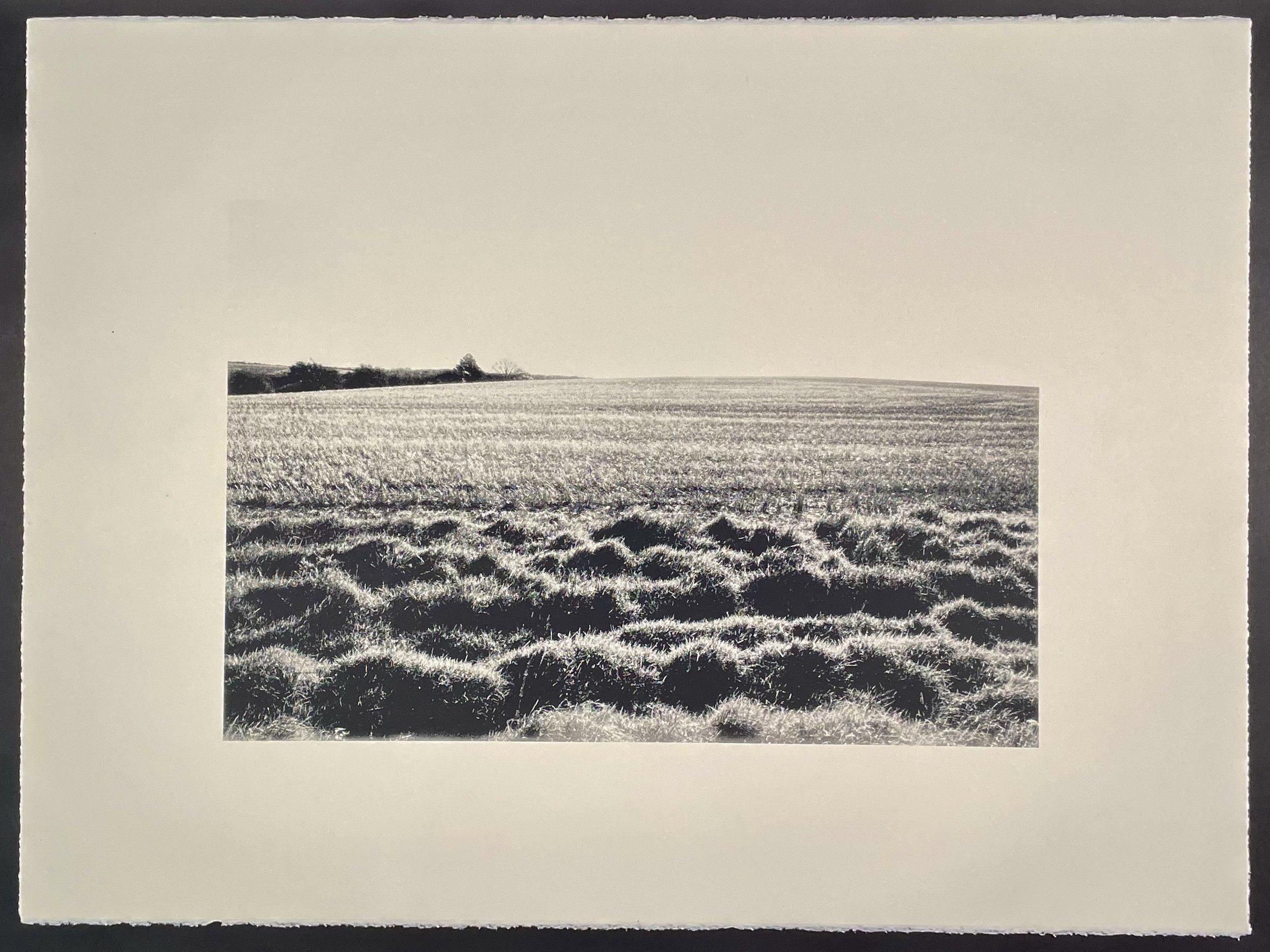

In my practice, screen printing explores the notion of the photograph transported into another medium. A photograph of an empty field, which in essence is a series of pixilations accumulated to represent a real place, shifts further into an arrangement of half tones. This breaks the view into a pattern of positive and negative tones that describe the landscape in a binary format. Flattening the depth of perception and uniforming shades between dark and light, create a code that indicate form but do not assume reality.

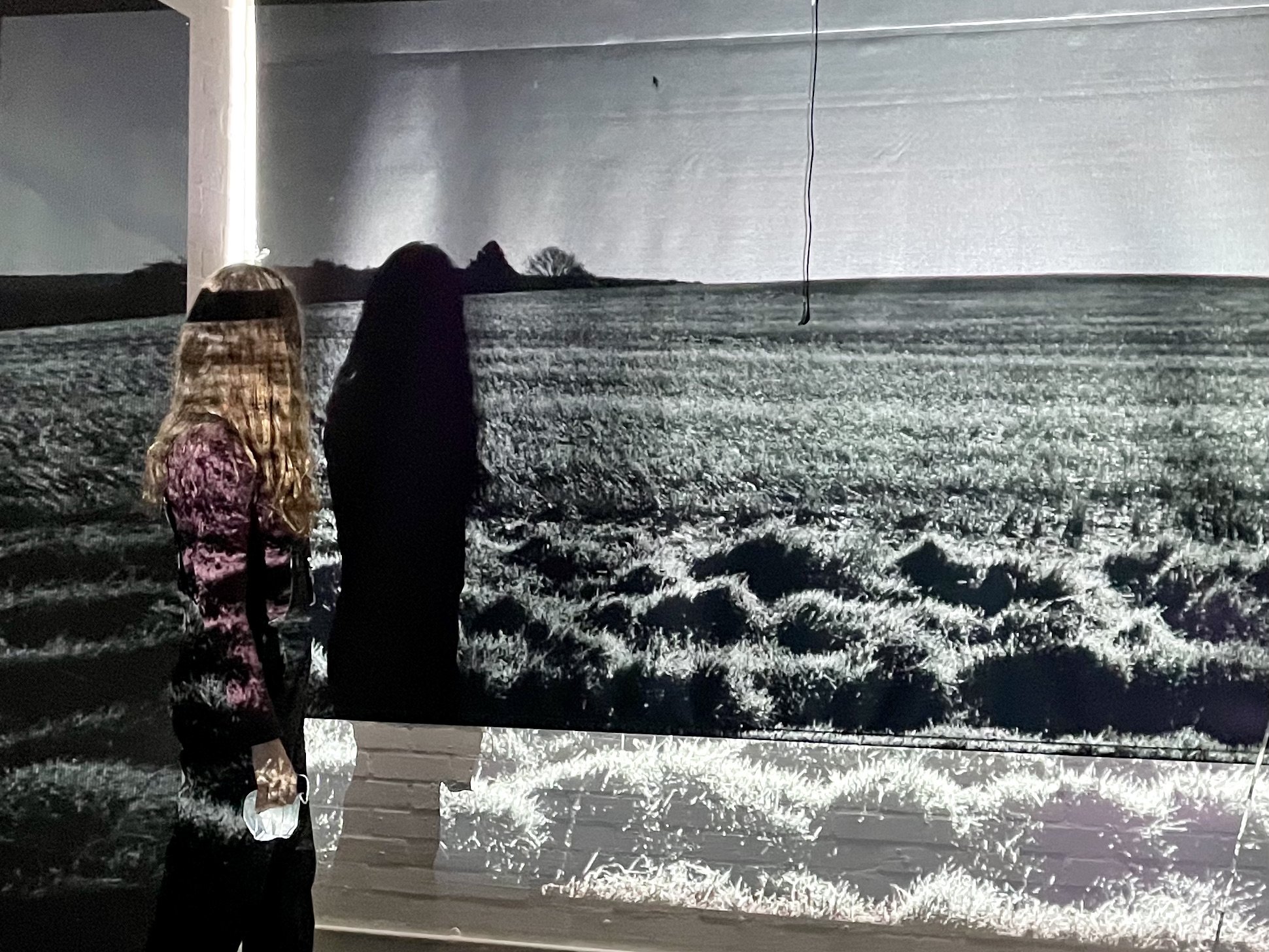

Scale is explored, learning technical processes in photoshop to increase the image proportionately within the context of the paper. Future aims are to enlarge the work further, to learn the skills in printmaking that move the work beyond the confines of one piece of paper, to many, joined together to make one large image. Previous work played with increasing scale by projecting an enlarged photograph of an empty field onto a drawing. This increased concepts of being in the landscape which is a key component in the practice. Methods of screen printing have the potential to explore scale, and it would be a new development in the practice worth exploring.

Experimenting with scale

Previous screen printing experimentation explored the use of the colour orange as a means to disrupt preconceived notions of landscape. The new prints are in black and white to determine the use of colour by experimenting with the lack of it. Henri Matisse talks about black as a colour. ‘Before, when I didn’t know what colour to put down, I put down black. Black is a force: I depend on black to simplify the construction. Now I’ve given up blacks.’ (2008:100). The practice often uses a monochrome or minimal pallet to avoid potential distraction and perceived meanings associated with colour. It had been a bold development to use orange in previous prints, but it seemed necessary to revert to black and white in order to understand why the work would or could use colour.

Drawing, making as unique

The screen prints, left as themselves, can be reproduced a multiple of times but this changes when drawing is introduced to the work. Mark making is a reference to presence in time and can only be created once. No copy or reproduction can be an exact replica due to the unique qualities of drawing. The marks on the screen prints are traces of nails and other small pieces of metal found in the ground.

Not looking to create but to re-create, the objects become a means to find arrangements where they can once again have a functioning future. Using the concept of a field as a grid to set boundaries and enclosures, the objects are given the opportunity to reconfigure a multitude of placements and uses. The work explores the earth, the soil and fields as an entity that holds not only the waste but living things. It sees the field as the hoarder of knowledge, containers of obscured and unknown traces.

Collaborative artists, Gill Gauri and Rajesh Vangad, combine methods of trace and photography. Fields of Sight (2013 ongoing) depict images of figures that stand awkwardly in both urban and rural settings overlaid with marks from an ancient form of Warli drawing. Gauri documents the struggles of everyday lives of nomadic communities in India (Suzuki: 2017), while Vangad’s marks narrate the stories that demand to be heard and provide the ‘missing vital aspects of what was not apparent to the eye’ (Gill, 2013 ongoing). The work combines ‘the contemporary language of photography with the ancient one of Warli drawing to co-create new narratives’ (2021).

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Women and Men, 2019