ESSAY: Field Works

Introduction

This essay introduces components of the practice which centre on observation and research as a form of methodology. With focus on the landscape as place and metaphor, Field Works considers concepts of time, presence and absence. It is directed by outcomes of conversations with unseen protagonists of the landscape through the discovery of matter and the collection of data. Field Works explores methods of performance in response to site and searches for initiatives which link activities across time. Testing outcomes on site and in the studio, the practice seeks an understanding of what it means to be present in the landscape. Martin Heidegger claims ‘being is not presence’ and Object-Oriented Ontology suggest ‘being is not present because being is time’ (Harman, 2018:201). The aims of current practice seeks to evaluate and examine this concept in relation to the work.

In this essay, philosophies of Object-Oriented Ontology provide critical reference to the love of wisdom rather than the possession of it (Harman, 2018:6-7). Down to Earth by Bruno Latour brings support for ecological awareness and the need to rethink concepts of belonging to a territory and John Scanlan’s book, On Garbage contributes critical references to concepts of garbage as evidence of understanding.

Responses to site are explored in a number of projects and the excavated objects remain foundational, emerging from the soil and directing the work’s focus towards the ground. Agnes Dean, Ana Mendieta and Cornelia Parker are included in the essay as key references explored in Field Works. Questions emerge around concepts of ideas and methods of presentation and artist research has been integral in directing elements of inquiry and development. As the work engages increasingly with the landscape, experimentation with objects in space deepen and research remains essential for critical development.

Fig. 1 Field Observation (2022)

Grids

The grid is a common component throughout this body of work, providing a safe space organised by straight lines which cross over at right angles to each other. A ruler, an instrument used for drawing straight lines, is also ‘a sovereign who controls and governs a territory. These two usages […] are closely connected’ in the way they regulate surface area by rule and dominance (Ingold, 2007:160). ‘Flattened, geometreticized, ordered,’ Rosalind Krauss writes the grid is ‘antinatural, antimimetic, antireal’ (1979). Any marks which travel outside of the grid are disruptions to the order and move towards notions of nature. Agnes Martin says, ‘the difference between nature and art is that there’s no perfection in nature.’ Her quest to follow perfection is demonstrated in her canvases which explore the grid through a multitude of outcomes. ‘I work so that all spaces are the same — are perfect’ (Glimcher, 2012:103).

The grid manifests in work using pencil and pen on paper. It is exploited with string as a guide for the work, Breaking Ground and fishing wire forms a framework that directs the development of A Field Guide to Leftover Matter. Seeking autonomy, this phenomena allows the work to make a fresh start. It aspires to rid itself of the clutter from past assumptions so that it may have ‘a sort of pure beginning, which makes its creation an exercise in freedom’. Bachelard writes, ‘Knowing must therefore be accompanied by an equal capacity to forget knowing. Non-knowing is not a form of ignorance but a difficult transcendence of knowledge’ (1994:xxxii-xxxiii). Object-Orientated Ontology echos the sentiments of Bachelard. It sees idealism as the true danger to thought because ‘reality is always radically different from our formulation of it. It is never something we encounter directly in the flesh and we must approach it indirectly’ (Harman, 2018:6-7).

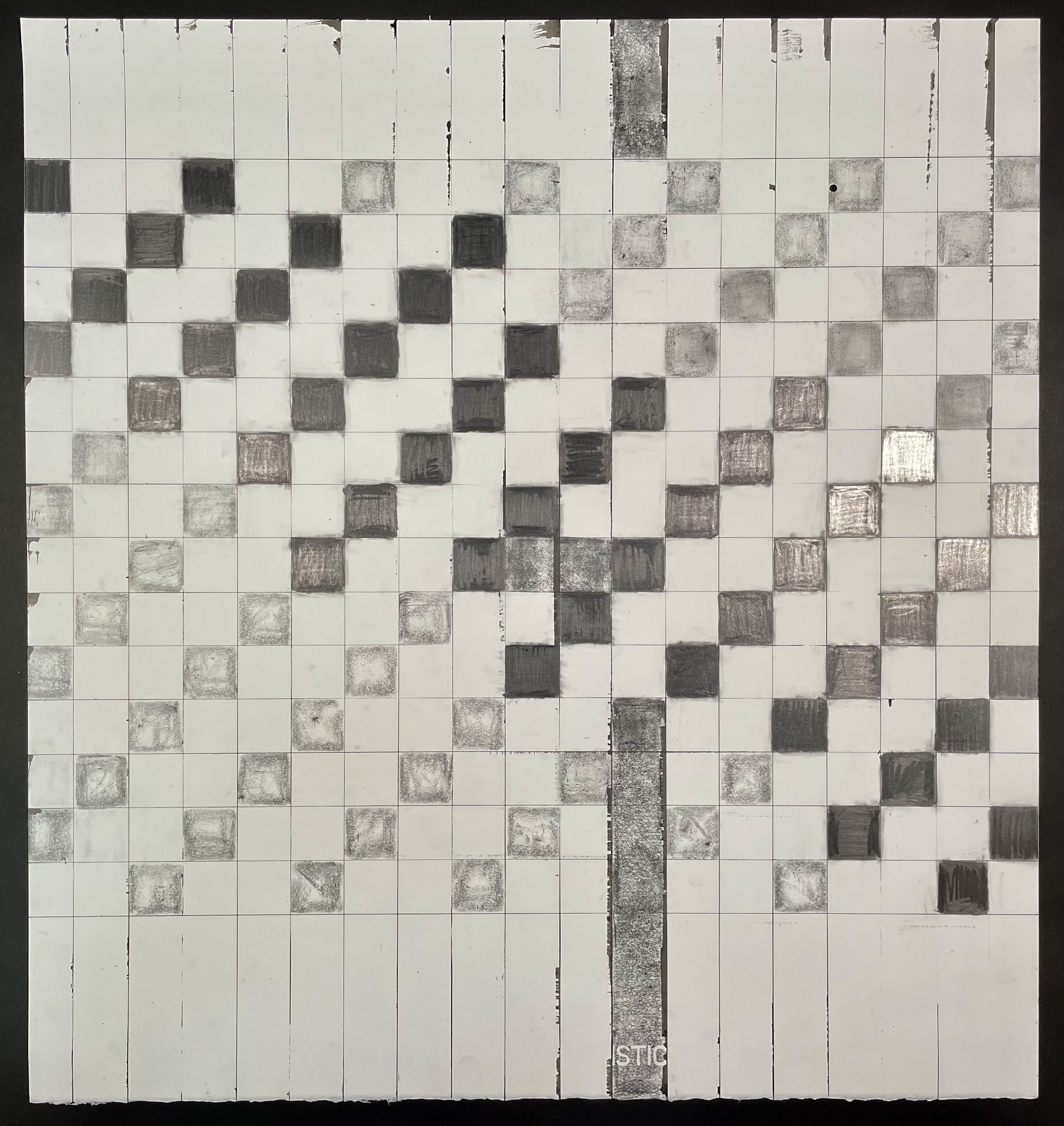

Concepts of non-knowing are explored in the pixilations of the screen prints. Providing horizontal and vertical structures, it is a space to explore where mark making has the freedom to disrupt order. Traces of pencil allude to leftover matter and play with and against the vertical and horizontal structures of the screen prints. Presented in a London crypt, Ground Cover I & II (2022) connect with unknown entities, once vital and useful. Imagined relationships and uses are revealed indirectly through marks on the prints. Reverberating with the ghosts of the Crypt, the unknown objects are revealed in a new context, bringing them new life if in a somewhat altered and unnatural state.

Within the perpetuating motion of sequences, the practice explores the grid in the timeline of Our Day at Alton and In the Field. Repetition and phrases divide the horizontal space vertically and a three dimensional grid forms to provide structure and limitations for play. This is also demonstrated in the form of a book, A Field Study, where rhythm and phrases, rules and order are arranged and assembled while moments of interruptions are free to infiltrate. Reinforcing Bachelard’s words, ‘a sort of pure beginning’ is facilitated by the grid and provides a space in many configurations in order to ‘exercise freedom’ (1994:xxxii-xxxiii).

Fig 7. Timeline, In the Field

Fig 8. Agnes Dean, The Tree, 1964, oil and pencil on canvas

Agnes Dean expresses how the grid provides tranquility and rest (Glimcher, 2012:104). She says, ‘Everything I paint is the same; there are no comparisons because each one is measured… each one is perfect’ (Glimcher, 2012:71). But Dean’s work is filled with imperfections. ‘The grid’s mythic power is that it makes us able to think we are dealing with materialism (or sometimes science, or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (or illusion, or fiction)’. This is the power of the grid, where logical straight lines perpendicular to each other release the work to depict illusion and imperfection, and transcendence of knowledge for the work to exist in. (Krauss, 1979).

Land Art

The Field Works series is associated with the land where care to observe and document takes precedence, but for the most part the work is presented in the studio or the gallery. Heathland Artworks, situated in Farnham Heath, provided an opportunity to develop a site-specific work in an outdoor space. ‘We do not obtain knowledge by standing outside the world; we know because “we” are of the world. We are part of the world in its differential becoming’ (Ingold, 2013:5). Breaking Ground (2022) explores this in relation to a distinctive sense of becoming, manifested in making through performance. Robert Morris describes ‘presentness’ as ‘… the intimate inseparability of the experience of physical space and that of an ongoing immediate present’ (2009:27). ’Ongoing’ and ‘immediate present’ are crucial for understanding Breaking Ground in the sense of shifting with time. To be present, it must embody a movement of being into the future. Being does not stand still, it ‘is not present because being is time’ (Harman, 2018:201).

Fig 9. Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Silueta Series

The works of Ana Mendieta were critical for the development of ideas. Embedding her body into the landscape, she would ‘push herself into the ground until she left her mark’. Experiencing separation from her home as a child, Mendieta craved a deeper connection with the world. Her close relationship with the earths surface resonated with the Field Works series and actions of digging. It identified with originating concepts which led the work to seek a close connection to place (Gottesman, 2017).

Breaking Ground explores a sense of becoming through processes that reflect particular characteristics of the heath. The people of the commons, identified with shaping the heathland, once cut its turf for fuel. Rather than ‘stripping the turves off the sand by the thousands’ they carefully took out every third turf in a row, and staggered the rows to create a chequer board effect. This maintained their resource (Howkins, 1997:23).

Revealing a relationship between human consumption and resource, the necessity for use but with care, was essential research for shaping the work. The grid formed by each turf, measuring 20 x 30 cm, became the guidelines for the work to unfold into. The excavated material became the components which built the stacks. These formed the monuments to this unique landscape, neither adding nor removing material. The negative spaces directly contributed to the positive structures and reflected the activities of turf cutting and the management of land lost to the contemporary world. Maintained through knowledge and care, Breaking Ground sought to leave the land so that it may be able to recover without harm.

Learning close to the ground provided potential vantage points where experience and first hand knowledge could unfold. Bruno Latour describes two concepts he calls Global and Terrestrial. The Globe

“grasps all things from far away, as if they were external to the social world and completely indifferent to human concerns. The Terrestrial grasps the same structures from up close, as internal to the collectivities and sensitive to human actions, to which they react swiftly. ”

He does not seem to advocate one over the other but describes them as two poles being almost the same. Latour debates both positive and negative characteristics, defining Global in terms of ‘to know is to know from the outside’ and Terrestrial as ‘considered from the inside, on the Earth’. But a Global perspective can lead to distortion and Terrestrial is associated with ‘imagination, … without grounding in reality’ (2018:69). One attaches itself to terms such as rational or scientific, the other, natural or imaginative. But he concludes the chapter with suggestions that as the planet moves away from the Terrestrial towards the rational and scientific, ‘we see less and less of what is happening on Earth’ as errors are made from a view point far away (2018:70).

Latour’s theory was useful towards understanding the development of the work for Heathland Artworks. It also echoed references to the grids association with materialism (logic and science) and belief (illusion or friction). Breaking Ground utilised the grid to allow space for a relationship with the earth as a terrestrial experience. It became aware of the quality of the soil, whether it was more or less sandy, or if one turf was full of roots and another crumbled on lifting. The turf alternated between dry and wet as the weather changed over time. On some days the conditions were hot and dry, on others wet and cold. The performance required a process of repetition as the mythic power of the grid directed knowledge and a closer relationship to the earth ensued.

Fig 12. Breaking Ground, Progress Day 8

Responding to Site

Predominantly, responding to site, was demonstrated in the Field Works series through the process of documentation in order to collect and transfer resources as evidence for research. Bringing the response to an indoor environment, Field Works demonstrates this through two specific locations. The first was Jane Austen’s House. Permission was granted to spend time in her home, to reflect on the significance of her presence, and to gain access to her artefacts and a library containing her novels and letters.

Jane Austen’s House

In her letters to her sister Cassandra, Jane writes about walking on a number of occasions. She mentions a social event in Alton, a nearby town, and includes a description of a moonlit walk home (Molland’s Circulating-Library, 2022). Movement through landscape as a form of mark making is an integral component in the practice and the work was keen to explore this passage manifested through time, body and space. Retracing Janes steps between her home in Chawton and Alton opened up a dialogue across time. It reflected on the changes but also the possibility of similarities between the two journeys

Fig 15. Our Day at Alton in Jane Austen’s House

Our Day at Alton (2022) is a stop-motion film from photographs repetitively taken every 6 steps for the duration of the 30 minute walk. Capturing the walk in the direction of the journey, the work is subjected to what is in front and present. Not beholden to this perspective, it observes a time when Jane occupied this ground but also alluded to a future where neither she nor the work are present. Counterbalancing this forward motion, the film eventually snaps backwards towards its place of origin. Moving in reverse through image and sound it begins again from the door of Jane Austen’s house, on a loop, the end of the journey remains unattainable.

A Field

The second site as subject matter for this body of work is a field that has associations with the location of gathered leftover matter. The soil, from where the objects have emerged, takes centre stage. Latour writes that, ‘each of us is beginning to feel the ground slip away beneath our feet’ as it comes to light there may be no planet, no earth, no soil, no territory and no longer an assured homeland for anyone’ (2018:4-5). Holding onto the land, empty fields are depicted as a symbolic gesture of presence as perceived absence.

Fig 16. Film Still (12 November 2021 07:18:24 12ºC light rain and a moderate breeze)

Fig 17. A Field Study, January - June 2022

Spanning a year from November 2021 to October 2022, daily images from one observational point, with date, time and weather, capture a field over time. The collected data is brought into the studio and forms the material for a series of works.

At the time of writing, Field Observation (2022) (see figure 1) and A Field Study (2022) are works in progress. Evidence of documentation is demonstrated in Field Observation as a list of collected data and A Field Study in the form of an artist book. They intend to highlight the mundane nature of everyday documentation. Where there are days with no evidence of documentation, a blank page or a missing line represent absence. Key to forming a sequence in order, the missing days and data are itself an empty ground. New technological skills, consideration of placement and scale, and the importance of paper are being widely explored. ‘Without needing to change their internal structure’, the works explore the image as experienced moments that emerge into new forms. (Harman, 2018:11). It becomes an object which simply depicts presence.

“In perceiving an object, one occupies a separate space - one’s own space. In perceiving architectural space, one’s own space is not separate, but coexistent with what is perceived. In the first case, one surrounds; in the second, one is surrounded.”

Where Breaking Ground is experienced and made on site, A Field Study is experienced on site but made off site. Both works use landscape as subject matter, but one is perceived as object, separate from the viewer while the other exists only in its surroundings..

In the Field (2022) is a digital film where the core sequence consists of a single 20 minute take from inside the field. Visually and audibly, it captures the long grass and evokes a calm and rhythmic sensation. Disruptions appear one minute into the sequence and thereafter every minute for the duration of the film. Selected field study documentation, sounds and leftover matter periodically intrude the horizontal flow creating rhythmical forms along the timeline. Technology distorts the stillness of the captured images to create complex layers of perception.

Fig 18. Film Still ‘In the Field’

Concepts of Object-Orientated Ontology suggest that objects come in two kinds. ‘Real objects exist whether or not they currently affect anything else while sensual objects exist only in relation to some real object’. The ‘real objects cannot relate to one another directly but only indirectly by means of a sensual object’ (2018:9). Interpreting the concept with the work, In the Field proposes that the core sequence of moving grasses is the sensual object while the interruptions allude to real objects. This suggests that the still images that weave in and out of the sequence relate to each other only through the rhythmic flow of the grasses. The depiction of long grass as sensation fills and links the spaces between the intrusions of data and leftover matter. Returning the framework to a comfortable and natural rhythm, the sensual object provides a platform for the work to exist.

Fig 19. Film Still ‘In the Field’

The encounter with objects remained foundational to the development of the Field Works series. It was appropriate to look at the works of Cornelia Parker who used fragments in many of her works as matter in its own form. They signalled that, ‘now any object, whether destroyed by the human hand, by natural processes or accidents could serve the artist as a means of engaging with the world’. The leftover matter is not confined solely as a way-finder to signal a route away from self-expressionism but is a source and means for research for gaining understanding of place and time (Scanlan, 2005:100). A Field Guide to Leftover Matter (2022) explores this concept, introducing the objects and the field as matter in their own form. ‘The found object is not a readymade, which is a new thing straight off the shelf, it already has a past, a pre-history’ and this is the essence of the work (Iversen, 2022:48).

Fig 20. Cornelia Parker, 30 pieces of Silver at Tate Britain on 12 July 2022

Blades of grass, gathered from the field, hang individually and inversely in A Field Guide to Leftover Matter, creating an upside-down world. Acknowledging influences gained from a recent visit to see Parkers work at Tate Britain, the grasses are arranged in a grid and placed in relation to the ground (Parker, 2022). Located within the sequence, leftover matter inhabits an elevated position, uplifted rather than invisible and concealed.

Fig 21. Development of A Field Guide to Leftover Matter

Parker’s work was often initiated by acts such as squashing, blowing up, or setting on fire. Her objects were put through a transitional process, which in her words, had ‘much more potential when their meaning as everyday objects had been eroded’ (Iversen, 2022;48). The leftover matter in this work has not been subjected to any further transitional process. Their moment of physical change had already occurred by the time of excavation and it seemed to serve no purpose for the work to enhance this. Rather, A Field Guide to Leftover Matter exposes the garbage in its found form. Perception is turned upside down and the objects are in full view. ‘In the resurrection and re-ordering of all kinds of garbage that furnishes the actual being-ness of existence’ (Scanlan, 2005:112) the leftover matter represents memory and engages in the world as objects once again. This does not suggest they have returned to an original mode of use as the process of rejection, entombment and resurrection has altered their meaning.

Fig 22. A Field Guide to Leftover Matter (2022)

“These material fragments, like all used-up and discarded objects, are no longer identical with any useful purpose, yet they do not disappear when consigned to the garbage”

A Field Guide to Leftover Matter introduces the objects to a mythical state of existence as memory is inclined to do and reveals a material longevity even when considered absent.

Conclusion

The aims for future practice intend to resume a development with working and presenting work in an outdoor space. Continuing to connect closely with the Earth’s surface in order to pursue an understanding of care, it supports the relevance of research to broaden development. Bruno Latour and John Scanlan have been key to comprehending meanings of ground and leftover matter. Their writings have enhanced notions of carelessness and waste, introducing possibilities of seeing matter and landscape in new and purposeful ways. Moving indoors, the work evolves in the studio and assumes the character of a Field Work. Film and sound have explored the landscape, playing with data collected through observation.

The practice intends to pursue concepts of working between science and illusion. Using the grid to provide the groundings for work to unfold, it is keen to continue to explore the freedom associated with its structure. Agnes Dean illustrates the immeasurable possibilities provided by the grid and the nuances that arise as a result of seeking perfection. Cornelia Parker upholds the use of found objects, endorsing ‘the things-in-themselves’ (Harman, 2018:255). The depiction of the object as itself introduces new concepts for the work resulting in outcomes of an installation nature.

Responding to the philosophy of Object-Orientated Ontology, the work aspires to gain knowledge not by possession but through the love of wisdom. Following a process of making, it hopes to gather nuances of understanding as outcome and to interpret concepts of being and presence in landscape. Altered and new perspectives may help to direct perceived understanding into realms not previously recognised and it is the objective of the work to push the boundaries of awareness in order to make encounters that might otherwise be in plain view.

Fig 23. MA Degree Show, Field Works at UCA Farnham (2022)

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Jacobs, R. (2022) Field Observation. [Digital print on paper] 432 x 2800 mm

Fig. 2 Jacobs, R. (2022) Exercise in Grid Formation II. Ink and pencil on paper, 56 x 60 cm

Fig 3. Jacobs, R (2022) Breaking Ground, Progress Day 3 [Photograph] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 4. Jacobs, R (2022) Fishing wire maps the space for A Field Guide to Leftover Matter [Photograph] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 5. Jacobs, R. (2022) Ground Cover II, 'Decrypt', The Crypt Gallery, London [Photograph, exhibition] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 6. Jacobs, R. (2022) Ground Cover I . screen print, ink, graphite and gel pen on paper, 760 x 570 mm

Fig 7. Jacobs, R. (2022) Timeline, In the Field [Screenshot] In possession of the author: West Meon

Fig 8. Jacobs, R. (2020) Agnes Dean, The Tree, 1964, oil and pencil on canvas. [Photograph, exhibition visit MoMA] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 9. Mendieta, A. (1976) Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Silueta Series [Photograph, land art] At: https://museemagazine.com/features/2017/11/20/w413qtz3xpqjl0lc2yzm1aar30395l (Accessed 15/08/2022)

Fig 10. Howkins, C. (1997) Commoners Digging Heathland Turf [Drawing] In: Howkins, C. Heathland Harvest. Addlestone. p.23

Fig 11. Jacobs, R. (2022) Breaking Ground, Progress Day 7 [Photographs] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 12. Jacobs, R. (2022) Breaking Ground, Progress Day 8 [Photograph] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 13. Jacobs, R. (2022) Film Still from Our Day at Alton [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 14. Jacobs, R. (2022) Film Still from Our Day at Alton [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 15. Jacobs, R (2022) Our Day at Alton in Jane Austen’s House [Photograph, Exhibition] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 16. Jacobs, R. (2021) Film Still (12 November 2021 07:18:24 12ºC light rain and a moderate breeze) [Photograph] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 17. Jacobs, R. (2022) A Field Study, January-June 2022 [Artist Book] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 18. Jacobs, R. (2022) Film Still ‘In the Field’ [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 19. Jacobs, R. (2022) Film Still ‘In the Field’ [Screenshot] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 20. Jacobs, R. (2022) Cornelia Parker, 30 pieces of Silver at Tate Britain on 12 July 2022 [Photograph, exhibition] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 21. Jacobs, R. (2022) Development of A Field Guide to Leftover Matter [Photograph, installation] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 22. Jacobs, R. (2022) A Field Guide to Leftover Matter [Photograph, installation] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Fig 23. Jacobs, R. (2022) MA Degree Show, Field Works at UCA Farnham [Photograph, installation] In possession of: the author: West Meon

Bibliography

Bachelard, G. (1994) ‘Introduction’ In: The Poetics of Space. Boston, Massachessetts: Beacon Press. pp. xv-xxxix

Glimcher, A. (2012) ‘Studio visit, October 8, 1974, Cuba, New Mexico’ In: Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances. London: Phaidon Press Ltd. pp.64-74

Glimcher, A. (2012) ‘Studio visit, January 23, 1978, Albuquerque’ In: Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances. London: Phaidon Press Ltd. pp.101-107

Gottesman S (2017) Ten Female Land Artist You Should Know At: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-10-female-land-artists (Accessed 17/02/2022)

Harmen, G. (2018) ‘Object Orientate Ontology and its Rivals’ In: Object Orientated Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Great Britain: Penguin Random House. pp.195-217

Harmen, G. (2018) ‘Object-Orientated Ontology in Overview’ In: Object Orientated Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Great Britain: Penguin Random House. pp.253-262

Harmen, G. (2018) ‘Introduction’ In: Object Orientate Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Great Britain: Penguin Random House. pp.1-18

Howkins, C. (1997) ‘Heather for Fuel’ In: Heathland Harvest. Addlestone. pp.22-23

Ingold, T. (2007) ‘How the line became straight’ In: Lines: A Brief History. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 152-170

Ingold, T. (2013) ‘Knowing from the Inside’ In: Making. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 1-15

Iversen, M. (2022) ‘On the Positive Value of Destruction’ In: Cornelia Parker. London, Tate Publishing. pp. 48-49

Krauss, R. (1979) Grids. At: www.jstor.org/stable/778321?sec=1&cid=pdf- (Accessed 01/06/2022)

Latour, B. (2018) ‘Thanks to America’s abandonment of the climate agreement, we now know clearly what war has been declared’ In: Down to Earth, Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 3-7

Latour, B. (2018) ‘The detour by way of history makes it possible to understand how a certain notion of “nature” has immobilised political positions’ In: Down to Earth, Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp.64-69

Molland’s Circulating-Library. (2022) Jane Austen, Her life and Letters At: https://www.mollands.net/etexts/lifeandletters/lal20.html (Accessed 7/03/2022)

Morris, R. (1978) ‘The Present Tense of Space//1978’ In: Doherty, C. (ed.). Situation. London: Whitechapel Gallery Ventures Ltd. pp. 27-28

Parker, C. (2022) Cornelia Parker [Exhibition] London: Tate Briatin. 19/05/2022 - 16/10/2022

Scanlan, J. (2005) ‘Garbage Aesthetics’ In: On Garbage. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. pp. 89-119.